All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

Inwardlistening MAG

"Do you see the eel in the wheelbarrow?"My father swiftly highlights the smaller word encased in the larger one with aleathery finger that acts as his yardstick in our makeshift classroom. My mind iselsewhere, meandering back to the display at the Natural History Museum,revealing the bones of one fish interred in the bones of another. I amremembering all the fish, staring back at me with their pinprick eyes, bearingteeth straight and narrow as the tines of a fork, their dried-out scales, thinand fragile as onion paper, glowing in the dimly lit air-conditioned hallway, asdark and dank as the sea's chilly infinite to a girl, not yet half her grownheight, whose small hand is growing gummy inside her father's larger one.

To tell it beginning with school would be foolish.

The story goesback further,

to words mingled with glass breath,

tumbling in arabesquesfrom a training tongue

and shattering in mid-air, a sound,enchanting.

My father is looking at me expectantly, so I focus withfeigned intensity. These reading lessons are an evening ritual. We clear thetable of our mismatched plates and bring out the McGuffy Readers, phonics drillsand twin pink books filled with lists of compound words. We do this so that I canhopefully start next year at a private school. From what I can gather, my parentsreally want this for me.

My father spends his days in a cramped apartmentabove ours, writing about education to the beat of the typewriter's shriekingartillery. On afternoons and weekends I sit contently at his feet, beneath thecollapsible plastic table that is his desk, and write plays about princessescrushed by elephants, or poems about families of rocks. I am beginning to realizethat re-reading my own writing inevitably makes my ears flush with shame.Occasionally my father will stop typing, lace his hands together behind his headand stretch, leaning back in his squeaky cherrywood chair. He will peer under thetable to ask a question about school, or once, to show me the inside of one ofhis books, a photograph of the author, his crooked gap-toothed grin spreadingfrom one wonky ear to another, like that of a beggar or snake charmer. This, hewould explain later, was Piaget, adding, "Isn't he scary looking, Grace?Would you like to be taught by someone who looked like him?" I came tounderstand that this was more a reflection of my father's distaste for Piaget'sreasoning than for his appearance.

I am still unclear whether my father'swriting was intended to morph into a coherent book, or if it were only for us.One thing I understood, though, was that I was his educational guinea pig, a roleI loved.

I cannot yet read my father's books,

adorning our shelveslike trophies.

Instead I breathe the manifold musty luxuriance

of brittleyellowed pages, tearing at a touch.

This is the reason I am readingand rereading the word wheelbarrow, trying to understand its syllables andintonation so that I can sound it out honestly with my eyes, ears and tongue allin agreement. It is a funny word whose concentricity seems to double back onitself, the convex wheel resting in the concave barrow - the first half of theword whizzing out of my mouth, with the second half somersaulting lackadaisicallybehind. It is the kind of word I want to holler down the drainpipe.

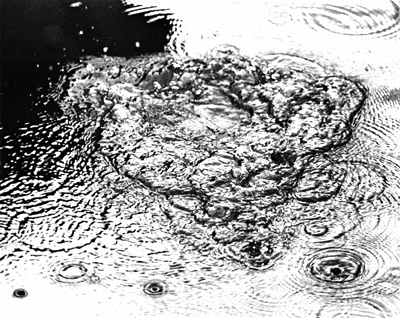

Myfather sees that this lesson is wearing on me, so he suggests a walk. Outside therain is falling in sporadic spits. Standing on tiptoe in front of the window, Ican see a few umbrellas blooming above the asphalt; they are gradually slickedover with the gloss of rain, making them gleam sapphire, onyx andtourmaline.

Neither of us tote umbrellas; we do not like to carry anythingand instead revel in freedom of movement. The rain quickly begins to pearl in myhair, soft and thin it hangs low on the nape of my neck. I try to imitate myfather's walk. Beneath his Greenwich Village uniform - a sheepskin coat, marledwool cap, and faded Levi's - he is as dignified as a heron.

We make ourway downtown toward the river. I leap over the deceitfully shallow-lookingpuddles surrounding each corner like a moat. When we reach the river, the rain isnearly done and the misty Hudson is redeemed by the orange light of early eveningshining down the brick of nearby buildings.

My father stands next to mewith his hands in his pockets like they're keeping him balanced. I notice that hehas let go of my hand. I am looking at him, and he is looking at theriver.

Across the waves where the twilight

deepens all the sky

at once, a transition, seamless

as the lining ofreverie.

My father gave me my independence in bits and pieces, entrustingit to me with the same care and consideration of one placing something preciousand breakable into a hand of unknown steadiness. I try to knot back togethersmall moments like these to give my childhood some kind of incremental coherence,but it is as difficult as recalling my grammar and spelling lessons atfive.

Years later, when I graduate from high school, after having triedthe full spectrum - public and private, traditional and progressive, coed andsingle sex, downtown and uptown - I will look back and feel thankful for thecross-section, however incomplete. Mostly, though, I will go out walking in thehours when the street lamps are warming into dusk and the city is infused with awomb-like familiarity, taking time to stop and read the crooked letters, e's likecurlicues, and a's leaning into downtown, that a child has scrawled on thepavement, with a smooth stick of chalk.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 1 comment.

0 articles 0 photos 12292 comments