All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

My Father, Wet Sneakers, Ant Cemeteries & the Blues MAG

Awarm hand closes around my wrist and my first thought of the day is of how gently myfather wakes me. When I open my eyes he is standing over me telling me to getready if I want to get a newspaper with him. For a moment I don't know where Iam. I'm not scared, I just feel like someone living another life. I remember weare in Rhode Island and staying at someone else's house which is why nothingaround me is mine.

As I shift out of bed the cold air stuns me as it doesevery morning. The hairs on the back of my neck rise and goose bumps begin tospread over my arms. There is a dull ache behind my right eye and I considersurrendering and going to sleep again in the nest of sheets and blankets stillwarm from my body. But I don't. My father is going to drive out for breakfast andthe New York Times and going anywhere with him makes me feel important. As Istumble around and get dressed I examine this room that isn't mine.

Thesunlight from the east floods everything, casting its brilliance over the chalkywalls and dirty cornflower-blue carpet. The bed frame is dark wood, and highenough off the ground to be intimidating. The overstuffed mattress is too smalland slides around when I try to get comfortable on hot summer nights. Theradiator is jammed between the bed and the wall, leaving a gaping hole which Isometimes slip into in my sleep. I wake up with my face pressed against a coldwall, my legs swallowed by the hole beside the bed and arms tangled beneath me.The jangling of my father's keys halts my rambling mind.

I tiptoe down thehall avoiding the black spots on the carpet by the kitchen where ants have beensquashed into it. The family who owns the house must have had some kind of antproblem that resulted in these burial grounds littering the floor. I carefullystep around them, afraid their bad luck may somehow be contagious. They make methink of Tuli Kupferberg, someone my father knew, who was part of the rad-rockgroup the Fugs, who lived in New York City and never killed a cockroach. Herefused to kill any of God's creatures. I guess sometimes having too muchhumanity can turn against you.

I rush to put on my shoes, tying themcarefully. I'm good at tying shoes, it's just something that came to meinstinctively, like blowing bubbles with chewing gum. I was not like the otherkids, fumbling with the thin laces in their clumsy hands.

My father iswaiting for me at the door, holding my sweater. He looks so tall and strong as heleans one sinewy shoulder against the doorjam. The light of the morning glowsbehind him, illuminating his shoulders and silver hair with a glorious light. Heis a deity in the simple room. I run to him, forgetting to avoid the antcemeteries underfoot. I stop in front of him as he bends down, his face inchesfrom mine. I raise my arms as he tugs my sweater over me. I grimace, rememberingthe ants. Now I will have to go the whole day with death on my shoe.

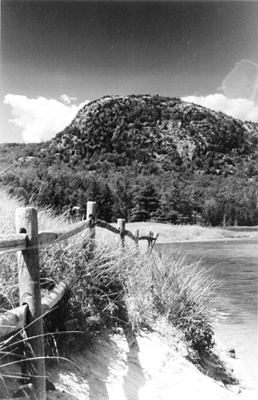

As wewalk down the steps I want to tell my father to lock the door in case robbers ormurderers come by while Mom is asleep. I know to keep my mouth shut, though.There are no bad people here. My parents are al-ready afraid I am too much of acity girl, so I have to try to pretend to be flexible and conform to this strangecountry life. My father points at the pearly mist dusting the trees.

"Look at that." he says, his voice electric in the still,morning air.

We get into the car, our wet shoes squeaking on the side ofour rented midsize. I grab hold of the door's handle and jerk my body back,making sure the door is closed. My father turns the key and the car comes alive.The radio begins to talk, the lights on the dashboard flicker, and the enginepurrs. I watch his foot sink on the pedal. His shoes are wet from the dew, likemine. He is wearing those lime-green Adidas shoes with ostentatious yellowracer-stripes down the sides. Some strange woman accidentally stole them oncewhen we were on the beach. I told my mother, and we chased her. I held mymother's hand standing behind her as she explained to the woman that she had justtaken my father's shoes. The woman was very embarrassed and gave them back; sheapologized, saying she didn't think anyone else's husband could have had the sameugly shoes. My mother wasn't offended, she understood perfectly. I wasn'toffended either. I was glad they loved their husbands, even in the world'sugliest shoes.

My father clicks off the radio. We are driving slowly now;the countryside grows before me, shades and shadows undulating beside the car. Awhite house with blushing pink shutters glides by. Tree limbs dance past mywindow, then a clean white house with robin's egg blue ornamenting the roof andwindows like icing on an enormous cake. The windows of all the houses aremenacingly vacant, like the empty dark stares of shark eyes. My father and I arethe only two people in the world. The city is never like this, and for a moment Ifeel lost, or betrayed by the silence of everything.

My father must sensemy discomfort because he switches the radio back on. I recognizeimmediately the soulful, salty sweetness of Lady Day as she croons "Let thepoets pipe of love, In their childish way, I know every type of love, better farthan they." I love my father's radio station where no one has a name,everyone is Empress of the Blues, Ol' Blue Eyes, Chairman of the Board, or theFirst Lady of Song. I sit on my hands and swing my legs because my feet can'ttouch the floor. The carpeted seat is familiar under my fingers, comforting and alittle prickly, like the soft part of a horse's nose.

We park evenly inthe designated space between two slightly crooked yellow lines. There are noother cars there, but we park courteously anyway. We get out of the car and myfather takes my hand. The tips of his fingers are soft and cool like new leather.As we walk a gust of wind blows by, filling my father's shirt and making itbillow like a sail. We walk into the little deli and a bell on the door janglesas it swings shut. My father picks up a copy of the Times and asks the man behindthe counter for a loaf of sourdough, coffee and a plain bagel. The man nods andgrins at me, a wide toothy grin, that makes the skin beside his eyes crease. Icarefully direct my gaze away and feign a detached fascination with the peelingBoars Head label on the counter. My father hands me the bagel and I sit on thewooden bench.

An old man wanders in. His walk is jangly and there is asadness in the way his clothes hang crookedly off his hips and shoulders. Hestands next to my father at the counter. My father says something to him I can'thear and the old man laughs in the heat of my father's charm. I just sit on thebench and watch my feet swing under me. I am not hungry but I eat my bageldutifully. I strain to listen to the radio. The static mixes with the twang of asitar, suspended in the air like a held breath. The old man turns to leave, awhite paper bag clenched in his fist. He looks at me and I smile graciously, asmile without a hint of sorrow for him or childish fascination with sickness orfrailty or age. He smiles back, an appreciative smile straining across his face.He waves as he leaves.

My father comes over and I take the bag ofsourdough bread from him. He tucks the Times under one arm and cradles a coffeecup as he holds the door open for me. We get back into the car as Nat King Cole'shusky voice fills the car with yet another torch song. My father sort of shimmieshis shoulders and does a little dance in perfect rhythm with the song. I cannotsuppress a smile. I look at my father once more before closing my eyes and losingmyself, wrapped up in all the pleasures of the morning.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 1 comment.

0 articles 0 photos 12292 comments