All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

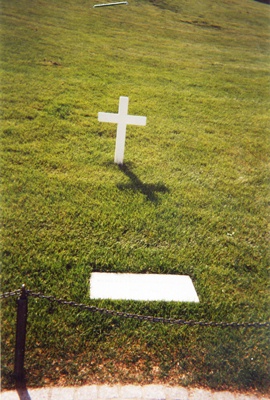

A Funeral

The day of my funeral it was raining. Of course it was. Great globs of splattering drops pounded down on the roof of the church, the sun choked behind bruised clouds. Little specks of mourners and a barrage of umbrellas trampled into the main hall, grime and the sky’s tears pooling over the gilded tiles. Grumbling complaints and the resounding sigh of people who wish they were anywhere but here rained down onto the silence of an empty hall with only the echoes of those dead prepared for their last celebration until the ground remaining. To my horror, not everyone who attended the service was wearing black. I knew I shouldn’t have invited Amanda Sultan and her outrageous sense of pink selfishness but that had been when I was alive, and I thought my funeral would be the grandest perfection of peaceful serenity.

I had been a fool when I was alive.

Finally, the mourners deigned to take their seats with more scuffling and shoving than a murder of crows. The priest gave the eulogy speech for none of the others were sufficient enough to tell my life story, and even he fell short with his over dramatic phrases and underdone somberness.

My funeral was open casket, of course, no need to rush the foreshadowing darkness of the grave when the people of my past could see my agreeable face once more. The mourners formed a line which became more like a snake slithering back and forth toward me as if ready to bite and sink its poison of boredom into my skin. The first mourner was Mrs. Carper, her bulbous eyes and bloated body bulging out of her scanty dress. She had been my neighbor when I was alive—an egregious one at that. When she stood over my casket, her engorged hands clasping her outrageously pink knock-off purse, she had the audacity to grin. “Good riddance you old bastard,” she hissed, flinging in a bottle of pest repellent I had used on her little yapping terrier that had tried to bite off a piece of my calf—into my coffin. As she passed she even spit on my perfectly shined shoes.

Next was my impudent nephew, Edgar.

“Hi,” my nephew murmured, scuffing the heal of what seemed to be brand new dress shoes. “Umm, yeah, so what’s it’s like being dead?”

I did not deign to respond.

“Yeah, uh, I know stupid question,” the infernally exasperating child continued, “well nice talk. Yeah, bye.”

Then came my brother in his crisp white shirt that was unbuttoned at the top, revealing a noticeable amount of chest hair that did not appear the least bit sexy since he was over fifty. “I can’t believe it,” he snickered under his breath, “you look even uglier in makeup.” My brother leaned in closer, close enough that I could smell the putrid stench of sweat and alcohol on him. “Rest in peace, jackass,” he finished and to my horror reached down and yanked my tie sideways. The insolent drunkard.

After him, a woman appeared, her eyeliner smudged, her greying hair left untied down her back. Her black dress was second hand with places of mismatched black threads where the dress had been patched haphazardly back together. It had been years since I had seen this woman made of a mirage of my childhood memories. She did not say anything, as if recalling those memories I had put in a glass jar that I hid in a closet in the far reaches of my mind. Then she dropped a single silver earing into my casket and left.

Foxworth girls were tragedies. They were golden masterpieces torn and unraveled at the edges, made of chemicals as deadly as Agent Orange (avoid with caution). Smudged red lipstick, sweat smeared eyeliner and ripped skirts too short, Foxworth girls were blessed by the devil (No trespassing unless you have a death wish to come in contact with atomic weaponry). With their tongues siren cursed to have snakes pool from their mouths, their bite was laced with sweet poison. Their smiles were as wicked as a cat’s and they may purr but they also have a tendency to not play nice with their claws. Deadly, Foxworth girls were not tragedies because they were rundown, scandalous blots on humanity like the churchgoing women believed, but because they were imperfectly, deadly creatures with their tattoos and piercings like flashing warning signs that only drew you in closer by their fiery tempers and sinful silver linings. Rule number one with Foxworth girls: never fall in love with one. They would take your heart and stab it with their iron-tipped nails and drink your heartbreak like fine wine. I, the incredibly awkward idiot, only took five minutes to break that rule. Since that fateful day when I was five playing on the swing set behind my school, I had been utterly, desperately, dreadfully in love with Jane Foxworth, the youngest of the string of Foxworth girls.

Falling in love is like loss: the loss of one’s control, one’s impulse, instincts, and of one’s heart over to the other’s uncontrollable epiphanies. That was why they said people fall in love. First, it would be the crack in the pavement, the half unfinished flirtations, then the terrifying trip as you saw the shy smiles lifting up the corners of her lips. Then it would be the fall, the crashing into that person’s waiting arms and open heart. For me it was like that.

It all started when I was eight at the swing sets behind the middle school. The day had been drowsily warm, the clouds bruised with rainclouds. I was alone leaning against the school’s brick wall waiting for my mother to come pick me up, when I saw her—Jane Foxworth. Swinging back and forth, she was like a robin flying up and dropping back down in the sky, up and down, up and down. Nervously, I had gone over to her. She had been crying. Ensconced in the swing next to her, I dared her to see who could swing upwards the farthest. She had agreed, that daringly dangerous dip to her lips burning with unspoken fire. In the end, I had lost, my whole mind too focused on a stray strand of hair that had escaped from behind her ear and was billowing in the wind. I had fallen off that swing set and hadn’t stop falling, crashing down, down since.

Until Jane Foxworth disappeared, leaving only a set of earrings behind in the dirt behind the playground.

The woman who dropped the earing into my casket was not Jane but an older Foxworth that I barely remembered explaining to me all those years ago about Jane’s kidnapping and had given me one of the earrings left behind. Now she buried the full set with me, as if burying the girl that would never have a grave.

Next, a wisp of a woman appeared before me with straight black strands of hair braided away to reveal a face with eyes sunken into her skull and skin stretching painfully over her cheekbones. Age had not been kind to her, the sleeplessness under her eyes like identical bruises as if she had gotten into a fight with life. She glanced down at me from behind black eyelashes that curled almost backwards into her eyelids. Looking away, she bit her lip, a lip that was swollen and scarred from years of the nervous act.

Then hesitantly, the broken woman slipped something into the pocket over my heart.

It was a ring.

The girl sat there waiting for something, waiting for nothing. Through the car window she was distorted like a picture that had been left out in the rain in the same way this lost creature had been abandoned at a bus stop waiting for something, an inevitable occurrence maybe that had been lost in the time waited. I only caught a glimpse of her, her hair plastered to her cheeks, raindrops trailing down her face like tears.

It had been years, no decades it seemed since I had seen her in this town, the girl who had been the envy of everyone, the girl who seemed to have it all. I knew I should have gone over to her, given her my coat or something, but seeing her there, alone and invisible like a closed door without a key, was too much for me. I wondered why she was there, why she had come back after all this time, why it was that her loneliness revealed that there was no one coming for her, that she finally was as alone as I was, as hollow as the empty bottles that scattered the floor of my apartment.

In the end, I didn’t go over to her, but went on with my life as if it had only been a second in time I had felt something again for the girl who had broken my heart three years ago and had left me without a trace. Weeks after that day, the scars she had traced onto my heart still hurt, the image of a girl that was as dead to me as if I had buried her myself still lingering on the outlines of my thoughts, the taste of rain and tears still fresh in my mouth. I never saw her again and I still didn’t truly know if I regretted letting myself pass her by. Yet it still remained, that second frozen in time snapped like a photo that had been found in the bottom of an old suitcase, a photo of a girl sitting at a bus stop, waiting for something, waiting for nothing.

“I don’t know what to say,” the broken woman whispered back in the church, slipping a strand of hair behind her ear as the funeral procession behind her started to become impatient. “I’m sorry,” she concluded, and walked away.

Then the silver woman approached my coffin like a slip of fog drifting over to a darkened cloud she had once belong to. A photograph, torn at the edges, the colors spilling together as if it had been left out in the rain, a picture that had been folded and refolded was poised in the palms of her hands—an image stained with tears.

She slid the photograph gently between my clasped fingers, like an Egyptian pharaoh and his scepter, and dissipated once more back out into the night morphing into the darkening twilight.

The house was built in 1873.

There was paint torn off in places of the house like worn out handprints placed against the wood for luck.

The woman painted her house the color of her soul, the color of her hopes and dreams, the color of a memory of an ocean she left behind with a boat and a country she would never see again.

The house was delicate and fragile like her bones but entwined and intricate like her thoughts built strong by unspoken words and feelings she could only translate in a language of dead trees and paint the color of a sky with no more clouds troubling her view.

The chimney was tall and lean like herself, the oak tree in the front as strong and old as the grandmother she remembered only as an afterthought.

The number was placed next to the screen door, 120, a magical number that meant nothing and everything to her. The lamppost, though out of place, she kept, like the lighthouse from her past and how it had guided the ship through the thrashing of waves and the storm of emotions roiling in her gut.

She carved the simple lines of stars into the outline of her roof, a small thanks to the stars full of wishes that kept her hoping and granted her a life she had given up on. The house was blue, like her soul, surrounded by brick houses stout and without a heart. Her house was blue, her house was her dream shaped and sewn into reality with nails and boards and a few wishes carved into the wood for luck. No one passing by would realize beyond the color that the house was different, that the house had a heart beating, beating, beating.

I didn’t know if that was the reason I picked it when my friends dared me to break and enter. I was half drunk, a bottle of wine with a bit of alcohol sloshing in the bottom of the glass grasped half-heartedly in my hand. Staggering towards the side of the quaint place, I picked up a stray rock from the gravel drive, feeling its sharp edges and unforgiving angles.

Then I threw it.

The side window shattered the night’s silence as it crinkled apart, jagged reflections of my pale face staring up at me from around my sneakers. My fingers trembled, the sound of a car horn in the distance snapping my body into a rigged pole. But I forced myself through the window, the edges of glass catching my fingers and elbows, marking me with pinpricks of painful guilt.

The blue house was practically as decrepit on the inside as I had imagined, missing all the scents and little trinkets of a warn in house that someone would call home. I must have broken into the study for a sparse writing desk and chair was shoved into the middle of the room, cardboard boxes full of possessions stacked in a circle around me. My eyes wandered about, searching for something that my friends who had goaded me into this would deem my breaking and entering a successful endeavor. But then my eyes caught on a worn photograph half folded and tucked under one of the brown boxes.

My fingertips grazed the gauzy skin of the picture of a time and a place and a woman frozen in the past as if I were holding the frail pieces of a broken memory in my hands. The not quite smiling woman stood before a little house made of redwood and painted a pale pink. The house was almost as petite as the woman herself as she looked up at the camera, her striking silver hair a blur across her face.

“You can keep that if you like,” a voice whispered from behind me, snapping the eerie silence of the unlived in house.

I whirled around, clutching the photograph to my chest.

The owner of the blue house herself was not blue but a silvery grey stained with two blushes of scarlet high on her cheeks. Her dress was blue, but a worn blue like the tied frothing against a gathering of doldrums. “That was my old home in Latvia,” the silver woman said, nodding towards the black and white photograph in my hand. Her thick accent sounded like wind whispering through the thorns of a rose bush in the middle of winter. “You can have it,” she continued, folded her arms carefully over her chest. “You can have almost anything left in this house to take back to your friends. I am going back home tomorrow.”

I gawk at the petite creature of frosted white skin and pale pink roses for lips.

“You do not need to explain,” she continued before I could attempt to form some embarrassing excuse for why I was in her living room. “I know what it is like to not fit in.”

I glanced down at the photograph before extending it to her, my fingers traversing the expanse of a silent sea between us. “I-I want to know more,” I stated, carefully, the words slipping off my tongue like a forbidden language I was afraid to speak.

After a moment, the silver woman nodded, slipping the photograph from my hands and placed it into the pocket of her threadbare dress as she started towards the kitchen where she made coffee and told me the story behind the blue house and the silver woman as I sat silently at a worn kitchen table, my blue coffee mug forgotten in my hands.

“If after tonight you still remember me,” the silver woman murmured, running a single finger along a strand of her hair, “I wouldn’t mind someone coming to say goodbye to me at the station tomorrow.”

I didn’t know what to say, so I just nodded. I helped the silver woman clean and put away the coffee mugs before returning to a darkened world devoid of blues and greys.

I did go to the train station that day. The steam from the train distorted my view of the silver woman, a waterfall of white curling over her, obscuring her gray eyes into a sea of black and white like the photograph she had given me but blurred at the edges. My heart was thrumming like a train at full speed, but I held my breath, waiting for her to reappear. Yet when the steam dissipated, all I saw was the last glance of a woman boarding a train with tears clouding in her eyes. Only then did I realize, I couldn’t say goodbye to a woman who I didn’t even know her name.

My final visitor was the priest himself, holding two small urns in each hand. “They would have wanted to be buried with you,” he explained as he placed each urn on either side of my chest. “They would have wanted the three of you to finally be together again.”

The memory began like this and ended just as abruptly, my young self unable to recall anything beyond the beginning of the end.

Headlights flashed.

Car tires screeched.

Glass shattered.

The world spun around me faster and faster until everything stopped as metal ripped across metal. Screams filled the air, but I didn’t know who it was or if it was me. I couldn’t see, couldn’t feel, couldn’t think, as if I was suspended in time.

I saw the tips of my father’s glasses slip off his nose and threads of my mother’s hair lift above her head like a halo. Then shards of glass and twisted metal hurtled towards us and then everything shattered.

I felt as if I was drowning in air, water churning around me, its weight pushing me farther into an abyss of darkness. Coldness seeped deep into my bones and the darkness beyond the headlights consumed me. That night so long ago, I walked away from the crash, but loneliness was my only companion, my only family dead.

The parade soon fractured apart, the begrudged mourners saying wisps of parting words before, with a click, they unlocked their car doors and went back to their individual lives without a second glance back at the body that had been their friend, their family, their enemy, their lover.

The grave diggers shut my casket with a final click, sucking out all the life left inside. The coffin jostled as the two men with a huff marched forwards into the silent darkness of my doom. When they dropped me into the bottom of my grave, my body jostled, the miscellaneous trinkets of my past that had been left to rot, to eat my soul for all eternity displacing all around me. Then the telltale sound of dirt being shoved onto my coffin resounded as the gravediggers began to bury a dead man alive.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 0 comments.