All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

Sugar and Smoke MAG

Mom always lit the candles on my birthday cake with her lighter. One hand holding the flame, the other tightly gripping the nicotine-filled lifeline to her sanity, she would envelop me in a hug that reeked of sugar and cigarette smoke. Happy birthday, sweetie. Mom was full of contradictions.

It was a sunny Saturday afternoon, the kind of day when mothers tell their kids to go outside and play. I remember the day because on Saturdays I had soccer practice. Usually I walked, but it was so hot that day that I really wanted a ride. Dad said he wasn't feeling well and couldn't drive me, and Mom was at work. I remember being really mad at him even though it wasn't his fault, the kind of irrational anger that twelve-year-olds are prone to. I think I was mad because it wasn't his fault. I stormed out the door, hair swinging behind me in a ponytail, and I ignored him when he called good-bye. The door slammed behind me.

Dad died when I was twelve. An aneurysm.

At the funeral, as I stood next to his casket and before an army of black-clad grievers, I remembered his laugh. He would throw his head back and give three long, deep bellows at something I had said or done. Always three, never less, never more. I used to wonder if he counted in his head, to make sure he was laughing properly. I did.

After they lowered him into the ground, the funeral-goers packed up and left. One less event to worry about on their calendars, one less person to care about in the world. Mom and I stayed to watch them cover him up. Every time a shovelful of dirt fell on the casket, I said good-bye in my head.

Thump. Good-bye, Saturday morning cartoons and ham-and-cheese omelets.

Thump. Good-bye, “South Park” after school before Mom got home.

Thump. Good-bye, reading late at night, Dad with a newspaper and me with Harry Potter. Thump. Thump. Thump.

I had planned to say good-bye to Dad himself with the last shovelful, but it came too fast and then there was nothing left but a small mound of uneven ground to mark where my father would lie. I never did get the chance to say good-bye.

Mom stopped telling me she loved me a few months after the funeral. When Dad was alive, he would say it right before I went to bed. Good night, kiddo. I love you. Mom would chime in with a similar sentiment, but I guess it was just a cheap imitation. With Dad gone, maybe she didn't know where to start. I thought about helping her by initiating the “I love you” myself, but I was never sure how Mom would react to further destruction of what had been her pristinely routine world.

Mom loved routines. Hers was wake up, go to work, come home with a takeout dinner, smoke a pack of Marlboro Lights, go to sleep. Lather, rinse, repeat. It was easier for her to fall back on something she could always count on than try to move on. It was my job to figure out my place in her routine.

I lived for school, for the eight hours it allowed me to be away from the silent tomb that was home. At night, during the hours it took me to fall asleep, I imagined that when Dad died, he was really being reborn. I imagined him reading the comics in his newspaper and giving his three-bellows laugh while Mom and I made a poor mockery of life in our coffin of a house.

On my eighteenth birthday, Mom helped me move what remainders of my childhood I cherished from her house to my new apartment in San Francisco, three hours from what used to be home. She complained about the smell, the stained carpet, and the noisy neighbors blasting Mexican music from a stereo next door, but none of her disgust registered with me. Having a place of my own was a breath of fresh air, even if fresh air itself was rather lacking in my new abode.

I think Mom worried about me. But more importantly, she worried about herself. She worried that with my newfound freedom, I would leave her to rot alone in that tomb. We said our good-byes that night in the middle of my new living room, surrounded by packed boxes and mosquitoes lured in by an open door. It felt final, and I think that somehow, we both knew we would not be seeing each other again for a very long time.

For the first time since Dad died, Mom told me she loved me. She wrapped me in her arms and murmured that she would miss me. For a moment, I pretended that I was a kid again. I allowed her to hold me as long as she wanted. When you are that close to another person, you can't distinguish their heartbeat from your own. I let Mom hold me, and as she did, I listened to our heartbeat. I said good-bye in my head as blood pumped through our body in steady, rhythmic pulses. Thump. Thump. Thump.

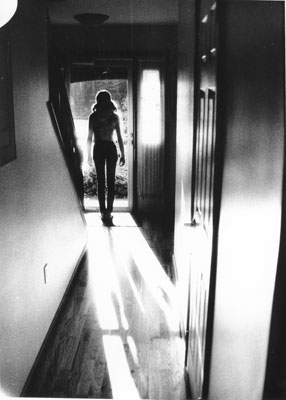

Mom released me and left me alone to my own heart and my new life. I never did get the chance to say I loved her too. On my eighteenth birthday, I said good-bye to sugar and smoke.

For some reason, even after she had left, I still smelled it.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 3 comments.