All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

The Beach

Sylvia knew that she had spent entirely too long looking at the different brands of cereal. She stared lamely at the rows of cardboard boxes, weighing the options in her mind. Should she treat herself and buy Cheerios, or stick with her usual choice store brand? The seventy cent difference seemed to hang in front of her in the air. Finally she reached out with an arm clad in cheap plastic bracelets to pick up the discounted O’s. She carefully placed them in her shopping cart and slowly made her way down the aisle, her feet shuffling on the scuffed tile floor.

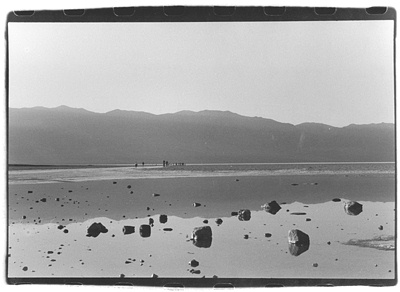

Creeping along in her car, a make and model long discontinued, Sylvia drove past the long stretch of decrepit beach that had come to define their town. Long ago, it had been a popular summer destination, a place where parents watched lovingly as their children splashed and squealed in the sea. Adorable breakfast cafes and surf shops had lined the streets. But no more. Now the once-picturesque beach was littered with trash, the shops boarded up and replaced with tenement buildings and adult movie stores. With the final downturn of the economy, the town had become a sleazy, grimy place where nothing much ever happened, and nothing much ever would.

After a time, Sylvia maneuvered the car into one of the narrow alleyways and parked in front of her building. As tenements went, the one where she lived with her grandson was a good one. Each apartment was outfitted with relatively clean water and electricity that only failed every so often, and as an added luxury, small balconies perimetered by iron fences. Of course, the balconies were sagging and their collapse seemed perpetually imminent, but Sylvia didn’t think too hard about that. Sylvia didn’t think particularly hard about anything.

Timothy waited for his grandma in the room that they slept in. In his boredom, he looked around the room, although he’d memorized everything in it long ago. It was a highly minimalistic room, utterly bare save for Timothy’s mattress in one corner, covered with a blue sheet, and Sylvia’s in the other, covered with a pink one. The floors were plain, rough wood which splintered his bare feet when he walked on it. The one decoration was a picture of Timothy, framed by carefully painted popsicle sticks and tacked to the white plaster wall. It had been taken by Sylvia at a petting zoo, a rare frivolity that she’d brought him to after his mother left him. She had thought that it might cheer him up. It hadn’t. In the picture, Timothy stared into the camera with somber eyes that seemed to droop with a timeless sorrow. Present day Timothy contemplated the picture with aching eyes that were a reflection of the ones in the image.

Presently, he heard the familiar bumping and rustling plastic that meant Sylvia was making her way up the stairs with her shopping bags. He trotted to the doorway, eagerly awaiting the first human interaction of his dull, lonely day. But when Sylvia reached him, all he received was an affectionate hair ruffle before she walked past him to slump wearily onto her mattress. He turned and looked at her with reproachful eyes.

“I’m so tired, Timmy,” she said, a well-worn explanation for her passiveness. Still, needy eyes looked up at her from underneath blonde eyelashes. “I know, let’s play a game!” Timothy’s ears perked. “We’ll play hide and seek,” she said. “I’ll count to fifty, and you hide, okay baby?” Timothy nodded gleefully. Hide and seek was one of his favorite games. As soon as Sylvia closed her eyes, he jumped onto his mattress and covered himself with his blanket. He giggled, and then promptly covered his mouth with his hand so as not to give himself away.

Sylvia stopped counting inside of her head. She didn’t know why she had started. She wiggled her hips, bouncing on the bed a little. Scratched her face. Looked over at Timothy. Looked at his outline under the blanket, a smooth, uninterrupted mound underneath the dirty blanket, like a hill. Looked at the blanket, resting on the top of his head and then falling in folds to his lap, where it puddled on his knees but failed to cover two dirty, pale feet. She looked at this pathetic form, and no overwhelming emotion overtook her. No love for this sad creature pulled at her heart. The only thing that she could feel was an overwhelming, all-encompassing weariness, sweeping over her like a tide. This wasn’t an emotion, or even a mood, but more of a heaviness. It weighed at her limbs, at her stomach, at her mind, making it feel as though her head struggled to fight against the gravity of her fatigue. She knew that she loved Timothy, of course she did, but she couldn’t find the love at that particular moment. It was somewhere, but lately it was buried under the layers of her tiredness too deeply to be extracted. There was also shame in the layers, shame for letting him down, shame that she wasn’t giving him all of the attention and care that he deserved. His mother should have given that to him, but she had felt the pull of the world beyond their town. She hadn’t been stuck in the void of the town like Sylvia, she had felt the lurking threat of complacency and apathy and gotten away from it, and for that Sylvia was proud. If only Timothy hadn’t factored into the equation.

Sylvia knew what she should do. She knew that she should keep counting, pick up where she left off, and then pretend that she couldn’t find Timothy, go through the monologue that all parents did at some point (“Oh, where is Timothy? Where could he possibly be? Where is that boy hiding?”). After an appropriate amount of time had passed, enough to make him feel smart for hiding so well, she should “find” him, and spend the day with him...make him a snack, maybe tell him a story....But she was so damn tired. She looked resentfully at the boy that she loved, and then her gaze drifted to the bottle of prescription sleeping pills resting on the floor next to her mattress... a rarity purchased for a considerable sum from an acquaintance who had, in the good days, worked in a pharmacy. They would deliver her from her guilt into the dreamless sleep she craved, a state of limbo in which there was no action which had to be taken and no expectations, her own or those of others, to be met. Tears pricked at her dry eyes. Decidedly, she unscrewed the childproof cap, picked up a white circlet from the bottle, swallowed it, and fell back on the sheet.

Timothy sat there, covered with his blanket, waiting for his grandma to find him, for hours. While he waited, he thought about what they might do when she found him. She’d probably give him a hug, he predicted, and tell him how clever he was. Maybe then they’d go make hot chocolate, and she’d tell him a story, and....

But time ticked on, and no arms took the blanket off of his head and wrapped around him. When the light coming in through the stitches of the blanket began to fade, Timothy unveiled himself, confused and and hungry, to see Sylvia passed out on her mattress snoring softly. An orange prescription bottle was nestled in her outstretched hand, its white, chalky contents escaping into her palm. Tears welled up in Timothy’s eyes and he wiped them away with a grimy hand, scolding himself. He didn’t know what he had expected.

He looked at his grandmother’s sleeping form. He twisted his fingers together, looked down at the floor. Then, almost without realizing what he was doing, he was walking out of the bedroom. Holding onto the railing and carefully placing both feet on each stair, slowly making his way to the exit of the building, and then pushing the heavy door open and walking out into the street. He paused for a moment to look around with unblinking eyes, and then turned to his right and began to walk. The amount of times he had been outside by himself could be counted on a single hand; Sylvia had lived in the town long enough to see what became of little children who were let to wander around by themselves in the streets. He didn’t know where he was going, his tired mind didn’t even contain a rationale for the direction he had chosen to walk in. His short, skinny legs carried him past signs in muted neon lights, past crumbling brick buildings, past people with ruined bodies crumpled against walls in a daze. He walked in a fevered desperation. Nobody took any notice of him.

Suddenly, Timothy arrived at the beach. He stepped onto the sand, so dirty that its yellow color had been diluted to a suspicious brown. A few people loitered around the edge of the water, but aside from that the beach was deserted. Out of the corner of his eye, Timothy caught a flash of pink. He looked over to see one lone food stand, a rickety blue table being watched over by a tall Indian man, selling cotton candy. Entranced (he was so hungry and the cotton candy looked so delicious-vibrantly pink and as fluffy as a cloud), Timothy headed towards it. The man running the cart did not look at Timothy as he approached. He stared straight ahead, a strange, half-smirk on his face. His eyes were utterly vacant. “Excuse me,” Timothy said in a childish voice that was scratchy from disuse. The man did nothing. “Excuse me?” this time, a little louder. The man still did nothing. Timothy blinked, bewildered. He took a couple of steps away, sat down, and stared at the ocean.

He stared at the brackish, undulating waves, and drifted into a daydream. He and his grandmother stood in a white space, dancing to no music. There was no rhythm to guide their movements, and so they were aimless. Limbs reached, joints bent, feet stomped and hands clapped awkwardly, striving to match some sort of tempo. But no soundwaves floated through the air to justify their desperate dance, to give it a purpose and direction. Still, together they stood, trying to catch onto a few notes of a melody. Their ears strained until their heads ached for something that they were not even sure could be heard, if it was there at all. Once in a while, an ear perked and a pair of eyes grew bright at the sudden detection of a note hanging in the air. But then it would fade, and the one who had heard it would be left wondering if they themselves had conjured it up out of pure desire. Sylvia and Timothy missed this melody they sought out, though neither one had ever quite heard it. Neither one had ever quite heard it, and yet still they danced. Without music, they kept on dancing in a space where time did not exist. They danced and danced and yearned for a melody, and they would keep doing so. Some small comfort could be taken in knowing that they were united in their plight, although greater than that was the fear that one should find it and the other be left without.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 0 comments.

The truth that I was trying to convey with this story was what it feels like to be stuck, bewildered and lost inside of yourself, unsure of where exactly it is that you are going. It is a feeling that everybody, teenagers especially, has experienced at least for a short period in their lives. I was inspired to write this story by a set of two images: one of a haggard woman outside a grocery store and another of a dirty little boy under a blanket. These pictures so strongly evoked the feeling of "stuck" in me, which drove me to try to express this truth.