All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

Belief

The day I saw my first ghost was the day I decided I no longer believed in God. I was ten years old, the same skinny, big-eyed kid I’d always been—tall, all limbs, as leggy as a colt. I had never been a particularly pretty child, with eyes too big and dark for my face, cheeks too hollow, skin too pale; many people would have said I was a ghost myself. Besides, I had recently been the victim of a butcher-cut by my mother, and my brown hair was sheared as short as a boys. This only served to make my orb-like eyes, and pale skin stretched over sharp cheekbones more noticeable. Many people described me as “eerie”, because paired with my appearance I was also considered too quiet to be trusted and too old for my age. People avoided me whenever they could. And this was before I could see dead people.

I was certainly lonely. I had no siblings and no friends. At ten, I already had a good idea about the social order in place even amongst us fifth graders, and that I was at the bottom. Home wasn’t a sanctuary, either. Although my mother still kissed my father goodbye in the morning and they spoke as politely as ever at dinner, I could tell they were having problems. There was nothing definite about it, no screaming arguments or frosty silences. But I was aware al the same that something had changed. Knowing this, I guess I shouldn’t have been so surprised when my father packed his bags and left. As I watched his taillights disappear around the corner, I decided that I no longer believed in a God that would allow someone so important to me to walk away so carelessly, a God who would allow families to be torn apart and hearts to be shattered to dust.

And then he came. He wasn’t transparent or anything, or bloody and dragging chains. He was just like anyone else, except that I had no doubt in my mind he was dead—not that I had known him in life. But I knew without a doubt that this man was my grandfather…except that everyone said my mother’s father had died after one heart attack too many over a year before I became a concern at all.

So, naturally, I was curious as to why my grandfather was sitting in my room, but to my credit I did not panic. I don’t know if I was in shock or still reeling from my father’s abandonment, but I calmly stared back at him, like dead people visited me every day. He had sagging bloodshot eyes like a basset hound, which were the same color brown as my mother’s. His skin was spotted and seemed to be slipping off his face, like someone had stretched it out long ago and he was determined it should still fit. It gathered on his neck, making him look like a turkey.

“Hello, Kara,” he said in a steady but slightly raspy voice. He sounded as if he had recently suffered a bad cold. “It’s nice to meet you.”

“Nice to meet you too,” I said automatically. My knees were starting to feel the weight of my surprise. It was one thing to see a dead person, but to have one casually talking to you like this was nothing unusual was something else. I sat on the edge of the bed opposite him and folded my hands in my lap.

He studied me. “I’d say you look like your mother, but I’m not sure that you do. You don’t really look much like either of your parents.” He stared at me a while longer; I couldn’t tell whether he was disturbed or fascinated by what he was seeing. I don’t think he could decide either.

I cleared my throat after waiting what I hoped was a polite amount of time. I tried to speak, but my mouth was so dry I had to peel my tongue from the roof of my mouth. I closed it, licked my lips, and tried again. “Can I ask you a question?”

“Another one, you mean?” When I just stared at him, he nodded. “Go ahead.”

“Why are you here?” I asked. I hesitated. “I mean, you’re…dead.”

He nodded. “Very observant.”

“Yes.” I felt a prickle of irritation now—after all, this hadn’t been the best day, and I felt drained. All I wanted was to go to sleep for a few hours. Part of me believed that when I woke up my father would be back, grinning at me with one side of his mouth more than the other like always, calling me “Kiddo,” and sneaking me a candy or small toy when my mother turned her back.

But this image of my father was an old one, because Dad had changed over the past few months. Not just physically, although he seemed to grow ten years in a span of the last few months, his hair graying, the corners of his eyes more lined. He also seemed to have less time for me, except for a perfunctory ruffling of my shorn hair every so often. Even knowing this, even suspecting the worst between him and my mother, I was stunned when I came home from school to find his bags packed and my mother sobbing on the couch. And when I’d asked him not to go, begged him, he only said, “I’m sorry, Kara—“(I was now Kara, not “Kiddo”) “—but I just can’t. You’ll understand…” He trailed off, shrugged, and then picked up his bags and left without even saying goodbye, or when he’d be back. I had raced to my window just in time to see his taillights rounding the corner.

My grandfather’s ghost was watching me. Something must have read on my face, because he looked concerned. I fixed my expression to what I hoped was impassive, and crossed my arms over my chest, like I was trying to shield myself against his pity. “Well?”

“I’m here to ask you a favor,” he said. I was relieved he was moving on and wasn’t going to question me about it. I didn’t want to talk about my dad, and I knew I wouldn’t know what to say, anyway.

“Okay,” I said slowly. But I didn’t want to help him. I had my own problems, and didn’t need to bother pleasing someone who wasn’t even alive. “But why can I see you? Aren’t you a ghost?”

“Why? Don’t you believe in ghosts?”

Don’t you ever just answer a question, I wanted to ask, but I restrained myself. “I…no, not really,” I said.

“Why’s that?” he asked.

I scowled. I was no longer concerned that he was a ghost. All I wanted was for him to leave, whatever he was, so I could crawl under my covers and hope all of this had been a very bad dream. “I don’t know,” I said tensely. “I suppose I don’t really believe in much anymore.”

His heavy black eyebrows rose slightly. “Well, that’s a shame,” he said gruffly, but he didn’t seem all that bothered by it. I wondered if this was an act, or if he sincerely didn’t care about me, as long as I did what he wanted. “Look, kid, I don’t know if I’m a ghost or a spirit or an alien. All I know is that I’m here, ain’t I?”

“Yes,” I sighed. Maybe it would just be easier to comply. “Okay. What do you need?”

“Take care of your mother for me,” he said. I hadn’t been expecting this. I thought it would be more complicated, like getting his will changed or recovering some long-lost item. “And tell her I love her, all right?”

“Alright,” I said, “but how am I supposed to explain how I know her dead father loves her?” I didn’t mean to be so blunt, but…my patience was waning.

“You ask too many damn questions, you know that?” He shook his head and mumbled something into his lap before looking up at me. “Not everyone is so doom-and-gloom as you, young lady.”

“What’s that supposed to mean?”

“’I suppose I don’t believe in much anymore,’” he mocked in a high-pitched voice. “What kind of a thing is that to say? Listen, young lady, not everyone has no faith. You tell your mother, she’ll believe you. Is that so hard to understand?”

I glared at him. “Alright then, but why should I help you anyway?”

“Oh ho!” He seemed to be growing increasingly amused by my anger. “You’re somethin’, ain’t you? You’ll do as I ask you.”

“Why’s that?”

“Because,” he said, “you’ll want to know if this was real or not, won’t you? See, you’ll go on about how you don’t believe in much just because right now you’re broken up, and it’s easier to claim to be a cynic than to admit you’ve been hurt deeply. But I think you want to believe in something—now more than ever, probably—so you’ll do what I ask.”

I blinked at him. I didn’t really know how to respond to this. Instead, I asked, “What should I tell her?”

His smile was too smug for my liking, but I tried to ignore this feeling. “Just tell your mother her daddy says he loves her, that’s she’s his moon, stars, and sun. She’ll get it if you tell her that. Moon, stars, and sun. Think you can remember that?”

I nod. “Is that all?”

“Yep,” he said. “That’s all.”

“Alright,” I said. “But…why can I see you? Is it all ghosts or just you…?”

He shrugged. “I can’t answer that. I don’t know. Just tell your mother, please. She’s hurting right now. Tell her.”

“I will,” I said. But I wanted to tell him that I was hurting too, and no one was trying to help me, were they? We all had our own problems to deal with.

He seemed to understand, however. “Look, I know you’re hurting right now. I understand that. You’re a good kid, Kara. Just don’t give up on everything just yet. You’re too young to stop believing.”

“Why?”

He smiled. “Because things happen in life that no one can explain. Look at me, right?”

I didn’t think this answered my question, but I didn’t know how to ask what I needed to know. I was too confused, my feelings too tangled. So I just nodded. “Yeah, I guess.”

You’ll tell her, then?”

I nod again. “I’ll tell her.”

“Thanks, kid,” he said. He lifted his hand, which was knotted like a tree root, in a parting wave before turning and walking through my bedroom wall, leaving only the faint scent of cigars behind.

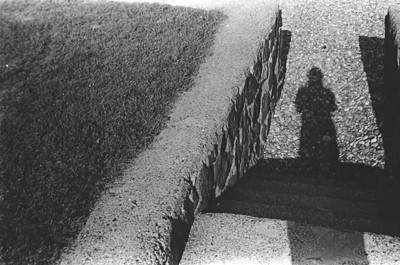

I got up and walked to my window, looking out into my neighborhood. Some lights in windows glowed in the night, like cat’s eyes in a darkened room, but no one was out. A faint wind ruffled the tops of the trees, which were so tall they seemed to brush the underbellies of the clouds. Winter was fast approaching, and the trees were bare of leaves, looking like skeletal hands stretching towards heaven. I could hear the TV blaring next door, and my mother doing the dishes before going off to bed. I could still smell cigars. I didn’t know what this all meant, what to believe or if it even mattered. In my mind, I could still see the ghost of my father’s taillights, rounding the corner and disappearing from sight.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 0 comments.