All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

Fluent in Silence

Someone once said that in order to open our minds, we must receive all around us like it is our own, but this is not as easy as it sounds. I was born in Hong Cun, an unpaved village with a two-figure population, squeezed in between the unfamiliar waters of the Pacific Ocean and the bustling world-class skyscrapers of Shanghai. It is a place where boiling weather calls for the start of days-long prayers for good harvest, and Thanksgiving is unheard of. Raised among people who believed our nation was the “Middle Kingdom”, the center of the world, I was expected to become one of them.

Nonetheless, I have always considered myself an American—a Long Islander, to be exact. After all, I have an affinity for scouting out the best bagel stores and delis in town, and firmly believe that ‘Long-Guy-Land’ has a language of its own. Really, I do. And it was the combination of all of these things that hampered my excitement at going back to my hometown for the first time in over a decade. I had imagined this trip to be nothing but a blur of loud talking, umami scents and tastes, and a rock-hard bamboo mat for a three-week’s worth of sleepless nights.

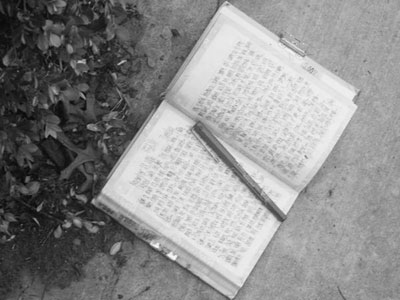

Let’s fast-forward three weeks. I am sitting cross-legged on my American brand name bed, tears streaking hotly down my face. A nearly empty box of Kleenex and my diary are within reach. I write that I wish I had never returned. I write that my heart breaks. It tears down at its own seams.

More than anything, it is the silence that kills me. When I lay my head down on my oh-so-soft pillow and my marshmallow of a mattress, the silence is tangible, no longer peaceful. It is a cold-stone slab that gives no answer to my sobs. I feel alone in the world, and upon remembering that my mother is in the other room, I cry harder, realizing that we are utterly alone in this strange place I had called home just three weeks ago.

Just like its bordering cities, Hong Cun is noisy, but disproportionately noisy to its undersized territory and population. By day, it was the very frail village elder, accompanied by a homemade walking stick, who trudged along the hardly visible breakaway path, hauling beside him a wagon overflowing with rubbish. The dust exhaust trailing behind his footsteps suffocated my lungs that had been unfairly accustomed to solely filtered, clean air. He yelped a few, short syllables in the local dialect, but I never bothered to make out the meaning.

There is always the noise. It is a cacophonous mishmash of the clanking wheels of rusty carriages, nonsensical negotiations in the marketplace, and whimpering babies fed up with the desensitizing heat. It is continuous in the sense of the ocean ebbing in and out on surf-polished stone, a scratched soundtrack forever in rewind. And I traced this strange, cultural lullaby that cradled me to bed: the laughter at the crack of dawn, the perpetuation of the village itself.

There was always light too; here, I was not afraid of the dark and its secrets. The Hong Cun people scare it away—the lantern rituals, the moonlight festivals, I welcome the light as the village people have always taught me to do. Slowly, this became my norm. The people I heard outside my cement dwelling I secretly befriended. I smiled and closed my eyes, while their voices unknowingly lulled me back into dreams.

While I had been cautious at first, I soon became eager to learn that it did not matter that I could speak only broken bits of the Hong Cun dialect. Smiles, touches, and laughter passed along the same mutual message with half the effort. The young baker down the bicycle alley, who weathered rainy days and a single motherhood with two infants, studied my face carefully as I handed her 5 Yuan. She stroked my hair, and with tired eyes thanked me for a generous tip that would constitute half her day’s pay. And I would come back, three times each day, three meals a day, rushing through the humid, unshaded streets to buy dim sum. Food is the universal language of Hong Cun, and dim sum is its official ambassador.

On the plane ride home, I once again played that same, familiar broken record of my summer. But this time, by choice, I rewind, fast-forward, pause, modify—I repeat until the images, sounds, and motions blur at the edges and spin into one web of a dream. I wave and shoot a friendly smile to the village elder, who makes his daily trek along the alarmingly steep and rubbly path. I circle the village gateway numerous times, following the trace of freshly-steamed buns, until I meet the warm gaze of the young mother. We are all after the same reality, trying to scrape a living to get by, competing to cooperate.

The complexity of these worn, yet striving villagers, as well as every individual in the world, did not have to be understood but accepted. Deciding to stop being so dogmatic, I armed myself with a new mentality and a handful of tolerance, and discovered interesting features that define this world. It is not important that some simply like their mother’s homemade meal more than McDonald’s, that many enjoy to drink hand-squeezed lychee juice than club soda, or that most would rather walk gravel roads than vaunt four-wheel drives.

I could not breathe—even without the thick, crowded air around me. I was simply amazed; I had missed so much because of my stubbornness. Neither the Travel Channel nor my fragmented memories of the past could have taught me that. It was after I rummaged my mind in search of familiar faces, berated myself, and felt something dense weigh down my chest that I learned we must be open to receive everyone in our lives. We are all human beings, and I can only hope that one day the entire world, even my beloved Hong Cun, will become as modern and advanced as New York.

For the time being, I have returned to the land of the lonely, where my mother and I eat dim sum together only on occasion, and she is the only one to teach me the ways of the world. I wonder why we came to Long Island in the first place when our home was flying by beneath our feet. I dare not ask her aloud, for surely her heart is breaking as sharply as mine.

So that brings me back to today, where I am still crying and no mountain of tissues can curb the flood. The house is quiet. The town is quiet. The world within me is quiet. I don't know when I will be able to look outside and marvel at the wonders of Long Island again, without being reminded of that part of the world that lies beyond oceans and skyscrapers. Do I feel traitorous? Only slightly, for Hong Cun to me is incomparable in its merits. The only thing that separates me from the other half of my double-identity is a 14-hour plane ride. But to me, it is the world.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 0 comments.