All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

The Secret Life of Boys MAG

Eighteen-year-old boys playing squash. Loud, smelly, and sweaty, this group of young men become my teammates from November to February every year. After four years of exposure to cursing, belching, and the concept of “adjusting” oneself, I have become somewhat immune to teenage boyhood, but I still find myself stricken with culture shock every time I realize that I have essentially become one of the boys. As a teenage girl, my hour of squash practice each night provides me with a fascinating look into the secret life of boys, a world where, biologically, I will always be an outsider.

A small square room marked with red tape, the squash court at Philadelphia Country Club is my gateway into a parallel universe. Within this secret world, normal identity and behavior dissolve into nicknames and “smack talk.” I am no longer Amanda, the quiet, awkward girl; I crush my given name to become Izes, an edgy athlete with sleek red safety glasses, midnight black sneakers, and no fear. Among the boys, I am a stronger, less self-concerned version of myself. My ability to compete with, and even beat, my male teammates rips apart the predetermined statuses we have established for each other within the confines of our school.

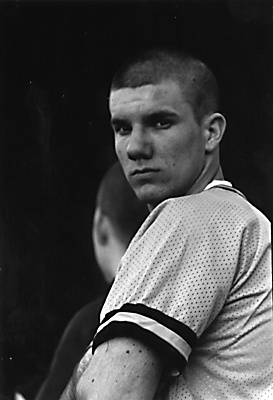

My acceptance into teenage manhood took place the third day of practice – much more quickly than it can take to be accepted by a clique of girls. Deliberately untying and retying my shoes to the perfect tightness, I waited for the rest of the team to arrive. At about 7:35, loud, low voices in the hallway indicated the arrival of my teammates, a pack of four I’ll call Jock, Techie, Slacker, and Savage. They had just come from Wing Night at the restaurant down the street. When they came into view, I noticed that the guys were still wearing our school’s uniform of polos and khaki pants. Naively, I assumed that they would head to the locker room to change; however, they began to undress right in front of me. These boys did not seem to care about privacy. They chatted about upcoming dances and parties as I averted my eyes from their Spandex and boxers.

While each team member has a completely different body type, no one comments about weight, height, or looks as girls would. In the boys’ world, because privacy is diminished, fear of others seeing and judging you or your body seems to decrease. My teammates’ lack of inhibition with each other is refreshing compared to the secrecy involved in changing in a women’s locker room.

I learned quickly that there’s a strong negative correlation between this absence of inhibition and personal hygiene. While I prefer the smells of vanilla and citrus, it has come to my attention that these boys enjoy, and may even take pride in, their own body odor. A healthy amount of body odor (described as “musk” by Jock) indicates to them that an athlete has accomplished hard work.

At squash practice, musk is, unfortunately, the prevalent odor. Because a squash court is only 21 feet wide by 32 feet long, the complex tends to trap smell. This stench appears to be part of the culture of masculinity – at least for teenage boys. Due to an apparent misconception of the science behind pheromones, my teammates, particularly Savage and Jock, believe passionately in their musk’s power of attraction. I can confidently inform any readers, male or female, that “the allure of musk” is a myth: I spend much of my time on the court breathing through my mouth.

Though my nostrils may never grow accustomed to their smell, I have observed that personal hygiene does play a part in the boys’ social culture. Unlike female groups, in which one girl may take on the role of mother, in male groups, no leadership or relational hierarchy seems to develop. Consequentially, few pieces of advice or guidance pass from friend to friend. This lack of communication can have detrimental effects on a group. For example, Savage, a lanky blond junior, unaware or uncaring of his pungency, grew more and more isolated last season. Savage eventually warmed up alone and talked minimally during practice, but remained unaware of the olfactory cause of his ostracism; no other boy cared to take on the responsibility of informing him.

I cannot help but compare my observations to the stereotypes of boys and girls that I have been taught all my life. I am programmed to think that because boys tend to be less cliquey, they are more welcoming than girls. As I watched Savage lose the friends who should have simply handed him a stick of deodorant, it appeared to me that while the dynamics of male friendship make it easier to make friends, they also provide little safety net in keeping them.

In addition, as an avid reality TV watcher, I had been taught that male competition, unlike the passive aggression of females, is expressed through trash-talking and physical rivalry. Anticlimactically for me, the competitiveness I expected from a group of athletic young men was missing. They seemed to have a strong aversion to any type of cardio conditioning. Instructed to sprint from one corner of the court to another 20 times, Jock, Techie, Savage, and Slacker jogged slowly with their arms limp at their sides. My teammates successfully avoided further physical exertion by locking our coach out of the court for the last 20 minutes of practice.

At the end of the final night of this season’s practice, I grabbed my bags, slowly exited the white court, and walked with Jock and Slacker to the parking lot. Gasping in unison at the assault of the frigid January air, Jock, Slacker, and I sprinted to our cars. Above the harsh slap of my shoes against damp pavement, I heard Jock shout, “See you later, Amanda!” I was reluctantly separated from the male world in which I had grown comfortable. With Izes left behind in the squash court, my time among the boys ended, and I was simply Amanda once again.

The next Monday, at school, I caught a glimpse of Jock, Slacker, Techie, Savage, and a bunch of other guys lifting weights in the field house. Clad in sweat-stained T-shirts and bright Nike running shoes, masking their musk with Axe body spray and their smack talk with blasting hip-hop music, they split their focus between lifting dumbbells and not-so-subtly observing the Spandex-clad girls’ volleyball team. The boys I had come to know over the squash season were puffed up with uncharacteristic masculinity. It seems that the need to flaunt one’s fitness to others mainly arises in the presence of the opposite sex. Much like girls’ desire for bigger curves and flatter stomachs to appear more attractive to boys, the extrinsic motivation for a teenage boy to appear stronger comes not from masculine competitiveness, but the motivating presence of young women. I now know from experience that boys do not inherently want to work out or have muscles of steel.

I have been taught all my life to consider boys and girls as opposites. However, after my immersion in teen male culture, I have reconsidered this idea. I originally expected that, upon entering the boys’ world, I would be struck by a strong wave of foreignness; instead, I found comfort there. Though the worlds differ in their smells, hierarchies, and support systems, the journeys of teenage boys and girls are parallel. Guided by insecurity, ambition, and oftentimes blatant sexual motivation, teenagers of both genders use the comfort of a unisex environment to develop their voices and personalities before releasing them into co-ed society.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 1 comment.

43 articles 2 photos 581 comments

Favorite Quote:

God Makes No Mistakes. (Gaga?)<br /> "I have hated the words and I have loved them, and I hope I have made them right." -Liesel Meminger via Markus Zusac, "The Book Thief"