All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

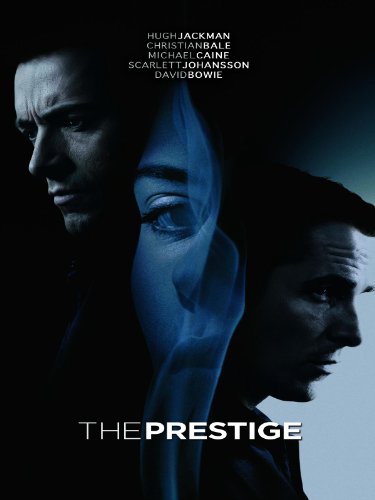

The Prestige

I’ll preface this review by saying that this is, by far, my favorite movie for a variety of reasons, so I might be a little biased. That said, let’s get into it. The Prestige is, in my opinion, Christopher Nolan’s hands-down, best work, and that’s taking into account the Dark Knight Trilogy and Inception, all of which are fantastic films. I think that the Prestige more completely accomplishes the sort of mind-blowing effect that Inception strove for, but does so with a more personal, subtle, and understandable touch. Most audiences coming out of Inception were confused by some, if not all, of the film, and it went way over the heads of most movie-goers in general. Those who did understand it however, will probably be keen to rave about it to you on any given occasion as it is the “golden child” of movies with plot twists, complicated metaphysical ideas, and just general astonishment. As stated before, I believe that where Inception falls victim to such pitfalls as making its plot too complex for the average viewer and having the mind-blowing aspect on a higher level of thinking, The Prestige is able to cut straight to the core of the idea and affect a viewer of any age or mental capacity because the plot is easy to follow, the characters have known histories and are extremely relatable, and the twist at the end is simple enough that it does not take a great deal of thinking to decipher. The story of the Prestige, being effectively and believably grounded in turn of the 20th Century London (and a little bit of Colorado), revolves around the lives and careers of two magicians who become rivals after one blames the other for the tragic death of his spouse. Christian Bale and Hugh Jackman bring scintillatingly nuanced performances to the table for this film, establishing a deep emotional connection throughout the movie between the character and the audience. (As a side note, I especially enjoy Bale’s performance because he finally gets to act in a movie that allows him to show off his British accent and not hide it like he has had to do for so many other films).

Nolan masterfully uses the structure of the magic trick in various parts of the movie, and effectively makes his entire film a magic show for the viewer. The opening and closing lines of the movie are parallels, both spoken by Michael Caine’s character, John Cutter: “Every great magic trick consists of three parts or acts. The first part is called “The Pledge”. The magician shows you something ordinary: a deck of cards, a bird or a man. He shows you this object. Perhaps he asks you to inspect it to see if it is indeed real, unaltered, normal. But of course… it probably isn’t. The second act is called “The Turn”. The magician takes the ordinary something and makes it do something extraordinary… But you wouldn’t clap yet. Because making something disappear isn’t enough; you have to bring it back. That’s why every magic trick has a third act, the hardest part, the part we call “The Prestige”.“ This 3-part magic trick structure can be applied to several scenarios throughout the film, including the entire plot as a whole. If we regard the events of the story in chronological order (which they do not appear in in the film), the story begins with James Borden and Robert Angier working as stagehands/plants for a stage magician alongside Cutter, an engineer of magical apparatusses required to perform various tricks. Borden and Angier are the ordinary somethings of Nolan’s magic trick, and this is the first part: the Pledge. The Turn begins after the on-stage death of Angier’s wife. Borden and Angier’s wife had long discussed changing the knot that they used to bind her hands for the water tank escape trick to a Langford Double; Borden argued that it would hold better for when the crane picks her up by it and places her in the tank. Angier rebutted, saying that it was not a water knot and that it could expand underwater, preventing her from escaping. At the performance following this discussion that the viewer has witnessed, Borden ties the wife’s hands (as he always did) and the trick commenced, but it became obvious after about a minute that, for some reason or other, she could not escape the bindings and was drowning. Cutter was able to smash the tank with a fire ax, but not in time to save her as she had already suffocated and died. Angier naturally blamed Borden for the death of his wife, but when asked whether or not he tied the Langford Double, Borden claims that he cannot remember and cannot decide which knot he ties. Angier refuses to accept this as a sufficient explanation for the cause of his wife’s death and thus the great rivalry between them was started. These two seemingly ordinary magicians go to all-out war with each other, and one could say that they go to extraordinary lengths to sabotage, injure, or discredit the other (Angier shooting Borden’s fingers off, Borden convincing Angier’s double to break Angier’s leg, etc.). Each also comes out with tricks that appear to defy all logic and reason and stupefy audiences, such as Borden’s Transported man or Angier’s New Transported Man (in which he appears to actually teleport). That right there is Nolan’s Turn: making Borden and Angier into apparently superhuman men driven by their intense professional pride and hatred of the other. Lastly, to discover the Prestige, we have to really determine what the Prestige is. In essence, it is the return of the ordinary something to its original state, the “bringing it back” aspect of the trick. For the Prestige, Nolan gives the viewer his big reveal in the very last minutes of the movie. The first is that Borden had a twin brother with whom he shared his entire life, each of them switching between being Fallon (Borden’s “manager”) or Borden, each of them having, as he puts it, “half of a complete life”. The second revelation is that Angier’s machine which he used for the New Transported Man actually duplicated him each times he used it, meaning that he had to kill himself each night he performed the trick, never knowing when he went in whether he would be the man who teleported or the man who drowned to death in a water tank. This takes all of the extraordinary motivations, actions, and logic-defying actions of the characters and reveals the simple truths behind them. This is especially the case for Borden, who throughout the movie appeared to exhibit behaviors which were exceedingly peculiar, especially his dual nature with regard to his wife, Sarah, who claimed that some days he loved her and some days he didn’t. His doting over her and her daughter one day followed by his getting in a shouting match with her the next is explained by the fact that he was, in fact, two different people: one who loved her and one who didn’t. This in particular grounds Borden’s strange and incredible life story with an incredible simplicity that gives the viewer an overpowering feeling of awe, disbelief, but at the same time satisfaction. These two revelations form the Prestige of Christopher Nolan’s grand magic trick that he plays on the audience: the entire movie as a whole.

Another aspect of this film that makes it really stand out in my mind is Nolan’s use of frame narrative and a muddling of the chronological order to tell the story in a strange, sort of lumbering way. The story is told in a sort of frame narrative: as one plotline is happening in the present (the trial/Borden in jail) Nolan splices in selected flashbacks (all the character backstory) in order to progressively give the viewer specific knowledge that is necessary to understand the story as a whole. As the movie begins, the audience member feels like they are trying to navigate a maze in complete darkness: stumbling over obstacles and blindly journeying down false passageways. This is because the viewer is constantly thrown from one time to another, one minute in the present, one minute in the past, and another even farther in the past. As a result the reader is given information piecemeal and is left to not only reconcile queer occurrences within the plot (such as Borden’s behavior) on their own, but also is left to try and develop a single, fluid narrative in chronological order. As the story progresses and the viewer gathers more information, that narrative begins to take a definite shape, and light slowly begins to leak into the proverbial maze that the viewer must navigate. The maze is only completed after Nolan gives us his final revelations at the end of the movie, and the viewer is finally able to connect all the dots with regards to the inconsistencies and paradoxes of the plot. In this way, it is as if you’re completing a maze on paper, and you know where it begins and ends, but in between you have only vague notions as to how the path bends or curves to get from start to finish. The lines are only drawn after the movie is over, and only then can the viewer determine how the whole thing really played out. This is the reason why I would conjecture that this is probably the most re-watched movie of all time: because after the viewer finishes watching it once, and they are given the lenses through which they must view the events of the plot, they can’t help but go back and use those lenses to grant a further clarity to their understanding of exactly what this movie is all about.

There are so many things that this movie gets right and so many deliberate decisions that Nolan makes to play the reader’s emotions to the benefit of his “magic trick”. One of my favorite instances of this is the parallelism that is exhibited between the journals of the two men. Borden writes in his diary: “Today Olivia proves her love for me to you, Angier. Yes, Angier, she gave you this notebook at my request. And yes, "Tesla” is merely the key to my dairy,not to my trick.You really think I’d partwith my secret so easily after so much?Goodbye, Angier”. In these lines and at the end of his diary, Borden directly addresses Angier, which is astounding to the viewer, because Borden was not supposed to have known that the book would be stolen in the first place. We as the audience had assumed that Olivia had truly stolen the diary for Angier to help him, but this unveils in a thrilling fashion that Borden was actually one step ahead of Angier the whole time. This scenario repeats itself later in the film, after Borden has been convicted for Angier’s murder and he is reading Angier’s diary in prison. The diary says: “But here at the turn, I must leave you, Borden. Yes, you, Borden, sitting there in your cell, reading my diary, awaiting your death,for my murder”. This, again, is incredibly shocking, more so probably than the first instance, because this implies that Angier had known that Borden would be convicted for his murder before he actually died. This line has a particularly chilling effect as the viewer slowly develops a grim realization that something not quite natural has occurred with regards to Robert Angier’s supposed death (this feeling is accentuated by the multiple ill-boding instances of foreshadowing that occur throughout the film, such as Tesla asking Angier if he had not only considered the price, but also the cost of his machine). Nolan’s use of a parallel scene construction here contributes to the overall impression that the viewer gets of the cat-and-mouse style of Borden and Angier’s relationship: their always trying to one-up or gain advantage over the other. These scenes also show Borden and Angier each having their own temporary moments of partial omniscience, which elevates them in the viewer’s minds and leaves us in awe of their craftiness, contributing to the “Turn” of the movie.

Up to this point, I have only discussed technical and organizational aspects of the film, but I believe that the most outstanding aspects of the Prestige are not its cinematography, but the philosophical ideas that it deals with. Perhaps my favourite of the arguments about life presented in the film has to do with escapism and the nature of the universe as it is versus how we trick ourselves into believing it is. In his dying breath, Robert Angier imparts his last bits of knowledge and wisdom upon Edward Borden, and he summarizes his entire philosophy on life in a few potent words: “You never understood why we did this. The audience knows the truth: the world is simple. It’s miserable, solid all the way through. But if you could fool them, even for a second, then you can make them wonder, and then you got to see something really special. You really don’t know? It was the look on their faces”. Angier expresses the idea that we as the general consumers of entertainment media so mightily embrace: the idea of romantic escapism. In a way, all of entertainment relies on one thing: the creative who develops the story must act as a magician, and their story must be a magic trick. Their duty as magician is to make us think, for maybe even no more than a second, that the impossible may in fact be much more possible than it seems. We want desperately to believe that the painfully ordinary world that we inhabit is, in fact, filled with the capacity for the extraordinary, and it is the storyteller’s job to make us believe it. Christopher Nolan not only accomplishes this within his own story, but he also manages to express the concept of it to the audience in a beautiful and moving manner, creating one of the most heart-wrenching and memorable moments in cinematic history.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 0 comments.

This review focuses on narrative construction and specific strategies utilized by the movie to create its overall appeal.