All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

Her Brain Was Replaced with a Tumor

I had heard of cancer, I knew people whose families were torn apart by cancer, but I had never seen it first hand; I had never seen it eat away at someone I loved, someone in my family.

“Do you want to see Auntie Connie today? It’d really cheer her up to see the family,” my mom said carefully. Little seventh grade me was eager to seem mature, so I complied.

Off we went to go and visit my cancer-infested aunt, my naivety an obvious display by the excitement I showed. I remember just before walking into the care center that my father pulled me aside while my mom continued on. The grave look on his face halted any questions that had erupted.

“Sweetie, Auntie Connie isn’t herself. The cancer is slowly spreading to her brain, so please keep in mind that she has no complete control over what she’s saying.”

I waved him off, saying, “I know Dad, I know what cancer does to you”, a weak attempt to show that I wasn’t a little girl anymore, that the knowledge I had gained from TV shows and movies provided me with an expertise of the disease.

His warning didn’t stick.

Once inside the doors, we went up to the front desk, and we gave her the name of the patient we were visiting. We were led down a hallway that looked like a sad attempt to create a homey atmosphere, but nothing could hide the open doors that led to IVs and heart monitors, or the sickening coughs that were met with an eerie silence.

Instead of a hospital, full of patients awaiting treatment and cures, it was a morgue, filled with the living dead, my aunt among them, residing in a room just like the rest.

Standing to the side of the doorway was my grandmother, or Nonni as I’ve come to refer to her as, who gladly approached us all for a hug. Upon hearing the commotion, my aunt Traci, and uncle Eric, arose from their seats by Connie’s bed to greet the rest of the family. Noticing we were lacking our usual number of four, Traci broke the silence.

“Forget you had another one again?”, She attempted to joke about our lack of my sister, Camille. We laughed half heartedly, appreciating the attempt.

“She’s got finals next week, so she’s doing some last minute studying,” my mother explained.

I secretly wished Camille were here now, just to have someone to distract me from what awaited in the room. Someone to feel the same way I did now: small and helpless in the face of a fatality.

Nonni wrapped one arm around my waist and bent down.

“Do you want to see Auntie Connie? She’s doing much better.”

I didn’t want to be rude and deny her, so I nodded reluctantly, and was led into the room that housed my great aunt. In a chair, seated next to her, was my Papa. Upon seeing me, he began to grin and said, “Look who showed up!”, while laughing softly.

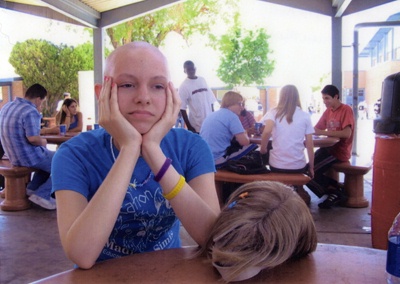

I peered around him and to the bed, where my aunt lie, frail, delicate as a loose petal about to be attacked by a merciless gust of wind. Her once full head of sun-kissed blonde curls were gone, replaced by a barren desert of crackled, pale skin. Her eyes were sunken in, along with her cheeks, with loose skin hanging around her face. She oddly reminded me of Darth Vader unmasked, which I shamefully shook out of my head.

Auntie weakly attempted to greet us with enthusiasm, but gone was the strong, healthy, and always a little plump aunt I’d come to know. She was replaced with a skeletal version of herself, one that shared a few characteristics, but developed them half-heartedly.

It’s one thing to see it on screen, to an actress or an actor whom you have no connection to, with the knowledge that it isn’t real. But to stare it in the eyes, to see the things it does first hand, is different. To see how it cripples someone who used to be so vibrant, so healthy, is different than just seeing a bald, flawless actor. To stare into the eyes of one in suffering, in pain, from cancer, when they’re used to be love and faith, is different.

Nonni gestured to an empty chair to the right of Auntie’s bed.

“Go on and sit sweetie, I’ve been in that chair for what’s felt like all day.”

I obeyed, and soon everyone had come back into the room. Dad took a seat next to me, and attempted to strike up a conversation of how she’s enjoying her stay.

“This one nurse always sneaks me cookies,” she said excitedly, “fluffs my pillows, too.”

I sat there quietly, staring at my intertwined, blue-polished nails, afraid of the sight laying in front of me. The conversations were a bore, nothing of interest worthy of me listening, so I would slowly tune out and every once in awhile revisit the discussion.

“There is no God,” Auntie suddenly began stubbornly and angrily. I was suddenly jolted back to the exchange going back and forth between my father and her. Everyone in the room was shocked.

Auntie Connie, the woman who would send my sister and I cards periodically throughout the year with scripture from the bible inscribed on it, had uttered these words as if it were the only thing she was positive of. My Auntie, the woman who would always sandwich my hand with both of her own and say, “May God bless you and keep you safe”, uttered these words as if it were the only thing she believed in. My auntie Connie, the woman who kept statues of angels and the cross throughout her house and visited church several times a week, uttered these words as if it were her new religion, as if it was what she prayed to every night.

“Now, you don’t mean that,” Nonni frantically said to her, clearly shaken.

This only angered the calm woman I used to know. “If there were a God, I would not feel this pain. If there were a God, He would’ve treat me better. I don’t deserve this. I devoted my life to God, and this is how He repays me?”, she spewed madly.

“He’s no God if this is how He treats me. There is nothing, no God, no Jesus, no Devil. I’d rather die than be here. I want to die,” she wailed.

My vision was swimming as tears pooled up over my shocked eyes. Mom, sensing that 13-year-old me wasn’t prepared for this, rushed over and pulled me out of the chair.

“Nicole’s a little thirsty, so we’re gonna go look for a vending machine,” she said hurriedly.

As soon as we were a fair distance away from that retched room, I sobbed and heaved repeatedly, shocked by my aunt’s harsh declaration of the disowning of her religion, by the way she so confidently disregarded the beliefs she had devoted her life to, how the pain and grief of cancer was so great that she believed she had been abandoned by the ominous force she was assured would protect her.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 0 comments.